When I made this blog I envisioned myself talking about how other people’s programs work. However, I’ve had plenty of people ask me how my own program CHOpt works, so today I’m going to talk about that.

As a quick note, I’m not going to go over my specific classes and functions because that would be boring and then I’d potentially have to update this. Instead I will go over the algorithm in broad strokes, pointing out some complications that have to be dealt with. Lastly, I will only be discussing guitar: drums has some details that I do not consider to be stable as of writing, and at any rate once you understand the core algorithm it’s not hard to tweak it for drums. The same remark applies to precision mode.

Overview

Clone Hero is a Guitar Hero clone first released in 2017. I’m going to assume you’ve played it before; while I’ll go over the key facts about the engine shortly, I’m not going to introduce the core gameplay modes and mechanics.

However, one mechanic I will single out is Star Power. Star Power (henceforth abbreviated as SP) is accumulated over the course of the song and can be deployed once you have a sufficient amount. For its duration, the amount of points gained is doubled. This means that if you want to get the best possible score, you will have to activate SP at specific times. A plan to activate SP at specific times is called a path. CHOpt’s purpose is to find the optimal path for a given song.

Review of Clone Hero’s engine

The details of how SP works is somewhat uncommon knowledge, so here’s what you’d need to know to implement CHOpt. The player has a bar or tank of SP. If the bar is at least half-full, you can activate at will. Surplus SP above a full bar is discarded. Once activated, SP will remain active as the bar depletes, all the way until the bar is empty at which point SP ends.

SP is acquired from so-called SP phrases. A phrase is a sequence of star-shaped notes. Provided the full sequence is comboed, upon hitting the last note of it one quarter of the bar will be filled. Any sustain notes in the phrase can be whammied for additional SP. Such sustains are called SP sustains. Whammying is binary: as far as the game concerns, you are either whammying or you are not. Whammying more vigorously does not award additional SP.

The amount of SP gained while whammying is down to how long you have been whammying. But time is not measured here in seconds, it is measured in quarter notes. For most songs this is equivalent to a beat, but not always. For example, if a song is in 7/8 time and you whammy for a measure, you get the whammy for 3.5 quarter notes rather than 7. SP gained from whammying is gained continuously, so you can start and stop whammying mid-sustain if the path calls for it. One quarter note of whammy fills 1/30th of the bar. Therefore, if you want to be able to activate after getting one phrase, that phrase must have at least 7.5 quarter notes of whammy.

Unlike whammy, SP duration is a function of time in measures. A full bar of SP lasts 8 measures, a half bar lasts 4 measures, and so on. An activation can be extended by hitting additional SP phrases and whammying SP sustains while SP is active. This provides an illustration of the distinction between how SP from whammying is awarded and SP duration. If you have a long SP sustain in 4/4 time, SP is active, and you are whammying, you will slowly gain SP at the rate of 1/120th of the bar per measure. If instead the time signature is 6/4, you will gain SP at the rate of 3/40ths of the bar per measure. Contrast this with when the time signature is 3/4 or 6/8, where you will lose SP at the rate of 1/15th of the bar per measure.

The other key ingredient is squeezing. In Clone Hero, you can hit notes up to 70ms early or up to 70ms late.1 This can be abused to get even more notes under SP, by being able to activate later while still getting the first note under SP and being able to squeeze in an extra note (possibly more) at the end. There are other rare circumstances where squeezing is useful in less obvious ways. The primary one is reverse squeezing. In that situation, you want to activate as soon as possible to not get the last note of a subsequent SP phrase under SP so it can be utilised for a later activation rather than prolonging the current one. You can buy yourself some more room by hitting the last note of the prior SP phrase early to activate even earlier, and hitting the last note of the subsequent phrase late. Sometimes this additional room is critical for making a path possible.

Abusing the timing window combines with SP sustains to give rise to early whammy. This is where you hit SP sustains early so you can start getting SP from whammy sooner. Clone Hero does nothing to disable SP accumulation from whammy before the note’s time, nor does it affect when the sustain ends. Thus this grants you more SP. For many songs, good early whammy is the biggest component of a good FC score from a path.

Lastly some words on sustains. Sustains continuously grant you points for their duration. Roughly speaking2, you get one point per 1/25th of a quarter note3, which is then multiplied by your current multiplier. So if you have a 4x multiplier, your score will go up in 4s during a sustain. Each such increment is called a tick.4 Changing multiplier (like due to activating SP) between ticks does not break up their atomic nature: you would go from +4s to +8s. The time you get the tick isn’t affected by hitting the note early or late, unless the tick is close to the note and you hit the note later than the tick. In that case, all ‘overdue’ ticks are collected the moment you hit the note. It’s also important to know that the last ticks of a sustain are grouped together approximately a quarter of a quarter note before the end of the sustain. So holding a sustain for the maximum amount of time is only crucial for getting maximum SP from SP sustains.

An example song

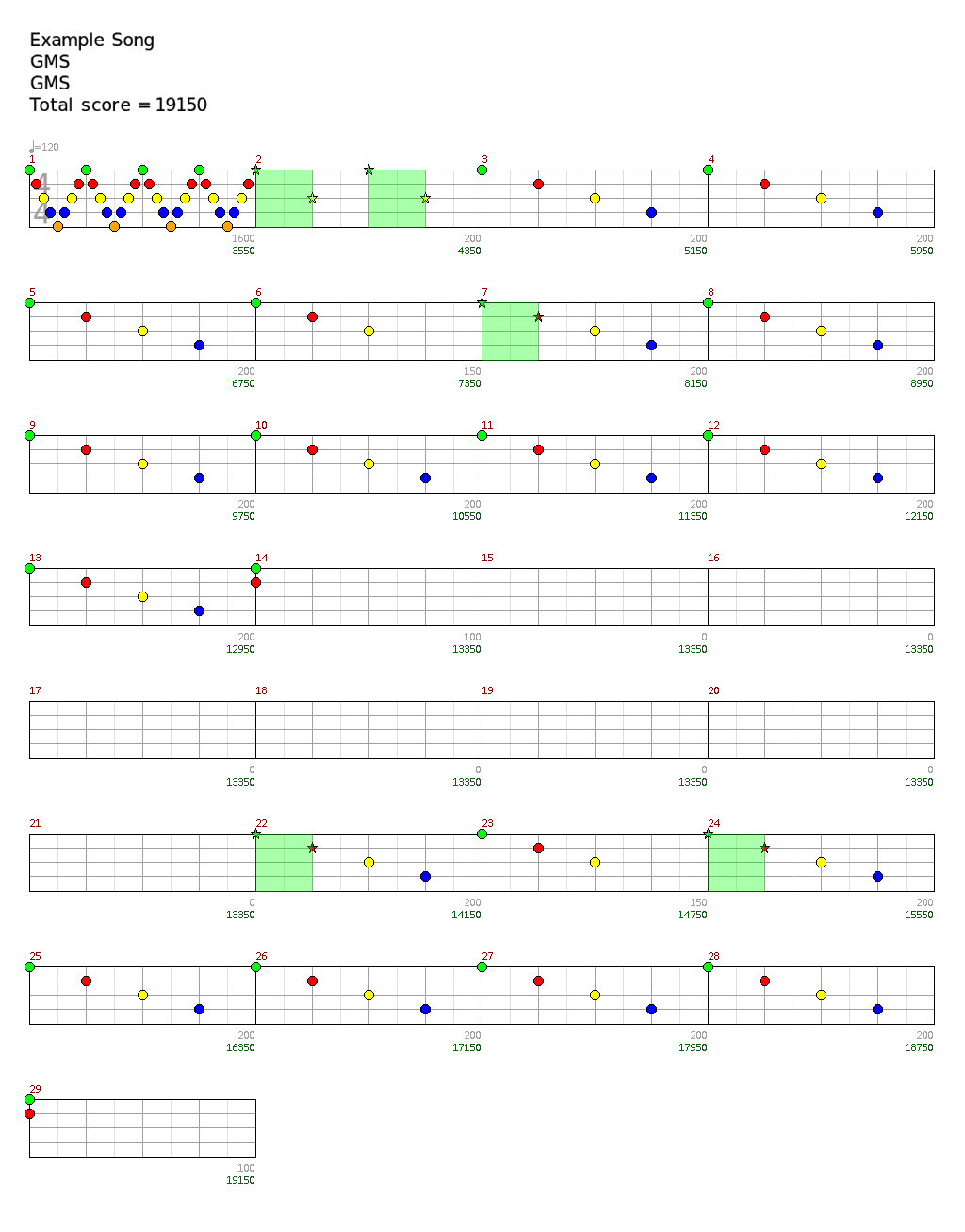

Rather than describe the algorithm in the abstract, let’s look at a simple example chart I made. To keep things simple, this song has no squeezing and no whammy, and is just complicated enough to allow us to focus on the core principles. We’ll start by coming up with an inefficient way of working out the path, then refine it.

Green regions are SP phrases. The 32 notes at the start are just to make sure we get to 4x before the first SP phrase, meaning we can ignore multipliers.

We shall start with a relatively straightforward recursive algorithm, starting from the beginning of the song. The earliest activation we can do takes us from the green in m3 to the yellow in m6. This activation gives us 3000 points. Then, the soonest second activation we can do after that goes from the yellow in m22 to the green in m28 (this is possible because we can reverse squeeze). This activation gives us 4400 points, so in total the path gives us 7400 points. If we did this path, then adding on the no SP FC score of 19150 would give us a total score of 26550. However, for every path the no SP FC score is going to be the same so there’s no reason to add it on until the very end when we give the user the estimated score.

Now obviously in general activating the instant we can is not going to be optimal. So this is where the recursion comes in. Let’s say we do the same first act. We’ll try the next possible second act, which in this case is the yellow in m22 to the red in m28. This grants 4600, so in total the path gives 7600 points. A sure improvement. Then we try the next second activation, yellow in m22 to the yellow in m28. This gives 4800, so a better path still. We cannot go from the yellow in m22 to the blue in m28, so now we move the beginning up a note.

Our next act would therefore be from the blue in m22 to the red in m28. Now we could calculate this, but you might have realised we don’t need to. See, we already did m22 yellow to m28 red, which is going to be strictly better since we’re starting on an earlier note and ending on the same note. Similarly we can rule out going from the m22 blue to the m28 yellow, and go straight to the act that goes from the m22 blue to the m28 blue. Calculating this gives us 4800 so just as good as our previous best path. Carrying along with this procedure, we go all the way to the end and discover that with our given first activation, the best second activation is from the green in m23 to the chord in m29. This gives 5000, so we now have a path that gives us 8000 points.

Now we go back and look at the first act again. We were starting with m3 green to m6 yellow. The next possible first act is m3 green to m7 green. This gives us 3200. Then we redo the step we did with the second activation to find the best matching second activation. Again, this turns out to be m23 green to m29 chord, which is 5000, so this path gives us 8200 points.

For our third potential first act, we do m3 red to m7 red… right? Except this isn’t possible, for the m7 red is the last note of a phrase and so extends our activation. Therefore, the true next activation we need to consider is m3 red to m9 green, which awards 4600 points. Then we have to find the best second activation that fits this. This search starts with m24 yellow to m28 red and ends with m25 green to m29 chord. It turns out the best of these is m25 green to m29 chord which gives 3600 points. In total this path is worth 8200 points.

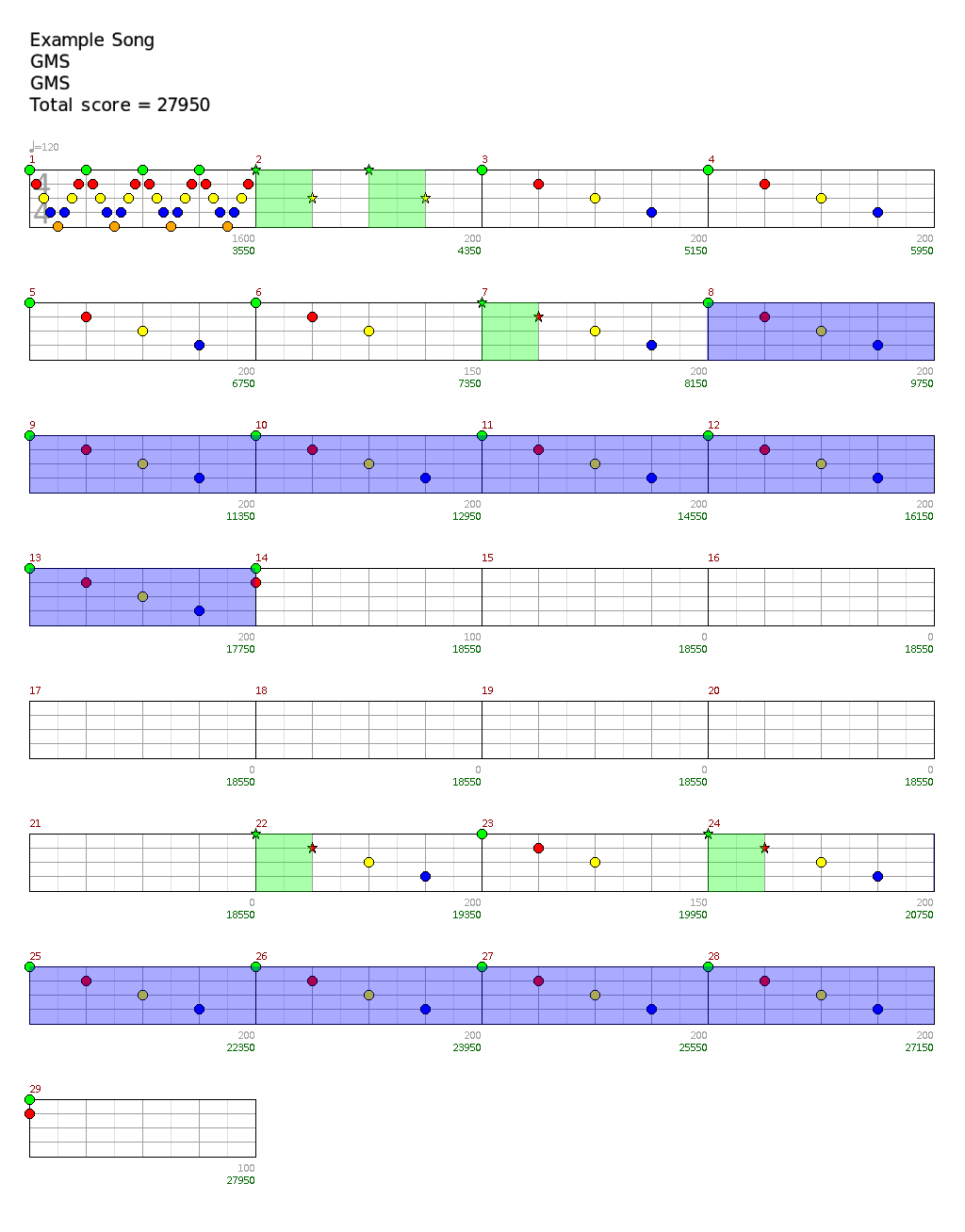

Then we do as first act m3 red to m9 red, and so on. Eventually this algorithm leads us to the finished product, our optimal path.

Activations are denoted with blue

Activations are denoted with blue

But why repeat yourself?

We have in our hands a basic algorithm that gets the job done, although it’s very inefficient. The next step is to make it respectable.

Notice that with the first two possibilities for the first activation, we got the same answer for the rest of the path. This is because both of those activations ended before the same phrase. Therefore whatever the best continuation of the path will be for one of them, it’ll be the same for the other. This observation is incredibly powerful and lets us dramatically improve our algorithm.

Once we’ve added an activation to the path, we count how many SP phrases are left in the song. If we’ve not already ended up in this situation, we diligently work out the optimal way to use that number of SP phrases. We then, crucially, store this information in some data structure of choice. If we have been in this situation before, though, then we know the answer and have it saved already. So we just retrieve the answer and append it to the end of the path.

This is a classic example of dynamic programming since we are using the solution to subproblems in order to solve our overall problem. The speedup is as dramatic as one typically gets from such insights. Done correctly, this is enough to get a usable optimiser.

To illustrate how effective this is, here is a sketch of what happens when we apply this to our example chart. Our initial first activation is m3 green to m6 yellow. Exactly as we did initially, we work out that the best way to use the remaining SP is to go from m23 green to m29 chord. This is the best way to use three remaining phrases. In total this path gives 8000 points.

Then we start with m3 green to m7 green, which also has three remaining phrases. So we use the answer to this subproblem we have, and now we have a path that gives 8200 points. Then we do m3 red to m9 green. Now we have two phrases left, and work out that these are best used to do m25 green to m29 chord. In total this path is also worth 8200 points. Next we do m3 red to m9 red, and are left with two again. Tacking that on, we get 8400 points. We keep going until we try m8 green to m14 chord, which combined with the last two phrases gives 8800 points.

Once we go forward a bit more, we end up not finding anything better before we start overlapping more phrases. Now we will end up with one or zero phrases left, not enough to give us an extra activation so the only thing we can do with them is nothing. Carrying on until we’re done with the song, we find the optimal path is the 8800 points one mentioned already and shown above.

One feature of this technique not apparent with this example comes into play once we have more than two activations. For we don’t just use this optimisation to handle the last activation. We can use it for the rest of the path, and even when working out the rest of the path for the first time, we end up accumulating lots of information to speed up even that process.

Another way you could make use of this insight is to work backwards. Start with the best way to use the last phrase: do nothing. Then go back and work out the best way to use the last two phrases. Then the last three, and so on, back and back until we’ve got to the start.

However, CHOpt goes with the recursion and memoisation approach for two main reasons. The first is that not all subproblems end up coming up. In our example, calculating the optimal way to use the last four phrases would be a waste of time since we can never arrive this situation. This point becomes stronger once we consider the effect of SP sustains, which I will discuss in a moment. The other reason is because it would complicate the second significant optimisation, which I will get to in a while.

Why it’s not so simple

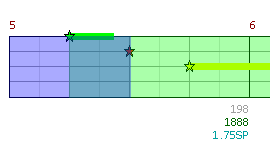

In our example, we were able to get by with only counting the number of remaining phrases. But obtaining a full phrase is only one way to acquire SP. We can also get SP by whammying SP sustains. This immediately raises a problem: what if an activation ends in the middle of a phrase and covers some but not all of the constituent SP sustains?

An activation ending mid-phrase

An activation ending mid-phrase

It is clear that merely counting the number of remaining phrases is far too crude. Perhaps we can only apply the optimisation in the case the activation ends before the next phrase starts? This would work provided we require the activation end at least 70ms before the next phrase starts, so we have the full amount of early whammy available. But this retreat gives up too much: activations ending mid-phrase are very common in optimal paths, and the vast majority of songs have the potential for them. And so long as the potential is there, we have to contend with it, even if in the end it may not turn out to be part of the optimal path. One could tweak this so our rule is that the act ends at least 70ms before the first SP sustain in the phrase, but this would be of only marginal assistance.

No, instead we must work out how to accommodate this properly. Think back to saving the subpaths. A natural way to view the structure used for this is a dictionary. The key is the number of remaining phrases, the value is the optimal way to utilise them.5 The problem is with our key, and that way lies the solution. We refine the key by making it a tuple of both the number of remaining phrases, and the number of remaining quarter notes of SP sustain left in the song. More simply, we can store this information as a position, taking the position the act ended and then moving it forward to 70ms before the next phrase if we are not already mid-phrase.6

Actually, it turns out to be better to use as key a tuple of position and the first point not under the act (moving this point forward like the position in a similar way). The main issue with just using a position is it adds a complication when SP runs out just after the last note of an SP phrase, and we hit said note late to not overlap. Using the position alone we would have to add in an auxiliary calculation that we are not far enough ahead to have hit the SP, and this is messy (messy and not even correct7). The majority of the time, this has the same effect as just using position so the extra strictness of our key does not cost us dearly in performance.

The second optimisation

With this optimisation done well, and taking some time with a profiler to find out what you’ve done poorly, you can get very far. Indeed, for a good while this is the position CHOpt was in. But then it starts getting viable to throw full albums at your optimiser, and while they generally do get handled, they take a while. Wouldn’t it be nice to have an idea that helps with these dramatically, while also helping with more typical charts?

Let’s think a little about what happens when we throw in a long chart. We’ll revert to our earlier version where we only counted the number of remaining phrases, a song with no squeezes or SP sustains. Let’s also assume our SP phrases are distributed roughly evenly, as is typical. Let \(N\) denote the length of our song (the specific units deliberately left vague) and \(k\) the number of SP phrases.

We will almost definitely have to work out what to do with the last two phrases. This entails, at a minimum, working out what to do starting with every point after the last phrase. This will take time roughly proportional to \({N/(k + 1)}\).

For the last three phrases, we will have to consider an activation starting with every point after the second last phrase, taking time roughly proportional to \({2N/(k + 1)}\). Similarly we go back and back to considering all but the first phrase (and we are likely to need to consider all these subproblems), giving us the sum

\[ ((k - 1) + (k - 2) + \cdots + 1)N/(k + 1) \]

This comes out to \(O(kN)\). For typical charts the number of SP phrases is roughly proportional to \(N\), so at a bare minimum we’re talking \(O(N^2)\). What can we do?

It turns out that in the process of doing this we will be repeating ourselves. Say our song has 100 phrases, and we want to work out what to do with the last 30 and the last 50 phrases. Once we are up to the last 26 phrases, in both cases we already have a full bar. From then on, the rest will be exactly the same. And so we have another opportunity for memoisation.

The trick is, when doing this process, track once you have acquired four SP phrases. At this point your bar is already full, and at that position it doesn’t make a difference if you have already collected four phrases or nine. So once we’re up to this point, from then on we find the best way to finish the path. We then store this in a data structure reserved for telling us the best way to finish the path if we are up to a certain position and we must already have a full bar. Then, in our 100 phrase song, when we start with the last 50 phrases we are likely done once we’ve collected five phrases, for then we can probably rely on the result we got up to this point when calculating the result for the last 49 phrases.

If you run through the back-of-the-envelope calculation above with this new optimisation, you get \(O(N)\). Since this is a lower bound, this is not to say CHOpt itself is linear: in fact that is definitely not the case because it does sorts and many \({O(\log N)}\) operations. But the calculation conveys quite well the savings on offer.

Looking ahead

After spending the time to make CHOpt nice and speedy, it’s tempting to try and make it even faster. But is there much point?

For typical songs, CHOpt now finds the optimal path so quickly that the majority of the time is spent in libpng saving the image. Making the process of finding the optimal path 50% faster would barely matter, and besides, it’s fast enough that for most charts users barely have to wait at all. While the image saving bottleneck might potentially be addressed by saving as SVG, PNG files are just far more convenient and it starts to feel silly at that level.

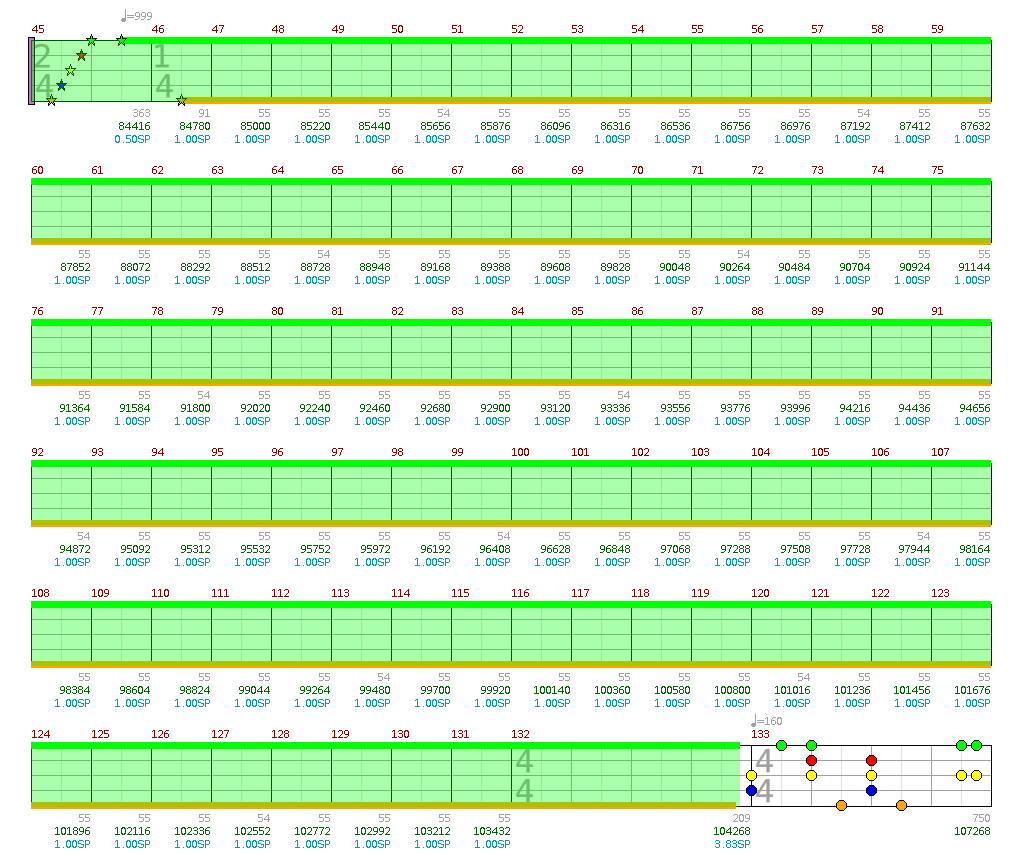

One major problem is exhibited by NFL on Fox Theme from Carpal Tunnel Hero 3. It’s a mostly slow ha ha funny meme chart that ends with an insanely high BPM SP sustain and CHOpt’s major optimisations don’t help here. To a human, the optimal path is easy to see. You can remove the big sustain and the path you get would overlap the start of it anyway, so the optimal path is to do that then just keep whammying until the song ends. It’s less clear how to devise a general way to spot this without some horrible hard-coding.

I think the way to go is to look again at the second optimisation and improve it. It doesn’t apply here because we just have the one phrase, and we can’t just change it to being able to get a full bar because on some songs it’s optimal to not always whammy SP sustains. But I feel it should be possible to tweak it by dividing into five, according to having zero, one, two, three, or at least four phrases, and in all such cases being able to full bar if desired. This should bring NFL on Fox Theme under control; well in a theoretical sense anyway. It’s obvious what the optimal path is, and the sustain is so long that the image file is too big to work.

Long SP sustains have been a thorn in CHOpt’s side before. Back when I made the original version, Sweating Bullets from Guitar Hero 5 was a big pain. Then I got it under control, and things were mostly fine until encountering Time Traveler from Circuit Breaker.

This happens twice, by the way

This happens twice, by the way

That aside, it would be nice to add support for other games and engines. CHOpt has support for Rock Band 3 guitar, and Clone Hero drums before it got changed again. I’m especially interested in the older Guitar Hero games and Warriors of Rock (including power-ups). While there are many differences between these engines, I am confident the core algorithm with these optimisations is robust enough to accommodate them.

Something else I’d like to do at some point is allow CHOpt to find paths that involve missing or overstrumming, when that’s optimal. Incredibly rare, but I am aware of one example in Clone Hero where this is the case with a chart not made specifically to exhibit this behaviour. This would require a slight change to the algorithm, where the key for the dictionary would have to also include the combo. Because the combo can be capped once the multiplier reaches 4x, this shouldn’t be as bad as it might sound.

On guitar, with no modifiers on. There is a wrinkle here: you can strum notes even earlier than 70ms without overstrumming or missing, and the game will register the note once the note is 70ms ahead. Matt, the lead developer of Clone Hero, has told me this leniency window is 50ms. This is useful knowledge for executing paths but does not affect whether the note can be hit under SP, so for the purpose of implementing CHOpt it is irrelevant. ↩

Due to a bug that cannot be fixed for backwards compatibility, the exact spacing between ticks depends on the resolution of the chart or midi. I shall not go into the details here, suffice to say that for your typical .chart chart it’s closer to 27.4 ticks per quarter note, and for your typical .mid chart it’s around 25.3 ticks per quarter note. ↩

I am ignoring extended sustains, but that makes no essential difference in what follows. ↩

Ticks aren’t a concept in Clone Hero’s code, the behaviour is entirely a consequence of rounding. However, they’re an invaluable fiction and since they perfectly reproduce the game’s behaviour, the little lie is harmless. ↩

One should also store the number of points granted to save having to recalculate it, but this is besides the point. ↩

I am glossing over some details of the calculation of the right position for the sake of clarity, but when implementing this these details become clear. There is further room for some tweaks here, but I do not feel them important or interesting enough to warrant discussion here. ↩

If the BPM is insanely high, the position need not tell us the number of remaining phrases. For instance, with a BPM of 13714 we get that four 4/4 measures take up just under 70ms. In general a very high BPM can give rise to lots of thorny problems due to breaking reasonable assumptions about the order of the times events can happen. I have not focused on them too much since they are so artificial, so if someone wanted to find mistakes in CHOpt this would be an excellent area to focus on. ↩